In the last three years, AMD has made significant progress with its Zen architecture. Consistently hitting its ambitious roadmap while rival Intel is mired with advanced manufacturing problems, there's very good reason to consider Ryzen for the desktop and Epyc for the datacentre. Performance is compelling and accelerating while value continues to be a cornerstone of AMD's philosophy.

It's easy to see why AMD has made meaningful incursions into desktop and server. Prioritising these two facets of computing has left the third, laptops, a little ways behind. The latest batch still uses the same overarching Zen architecture as its segment counterparts, but they're not on the same leading-edge process. In contrast, Intel, which holds the lion's share of the mobile x86 market, is empowering its latest laptop silicon with its best manufacturing.

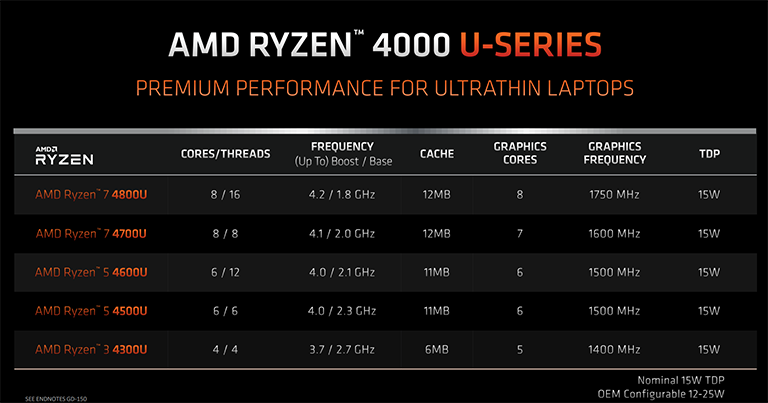

That situation, however, changed when AMD announced the Ryzen Mobile 4000-series family of APU at CES in January. Codenamed Renoir and soon to be available in in U-series (15W) and H-series (45W) forms for ultrathin and gaming laptops, respectively, let's take a closer look.

Renoir architecture - CPU

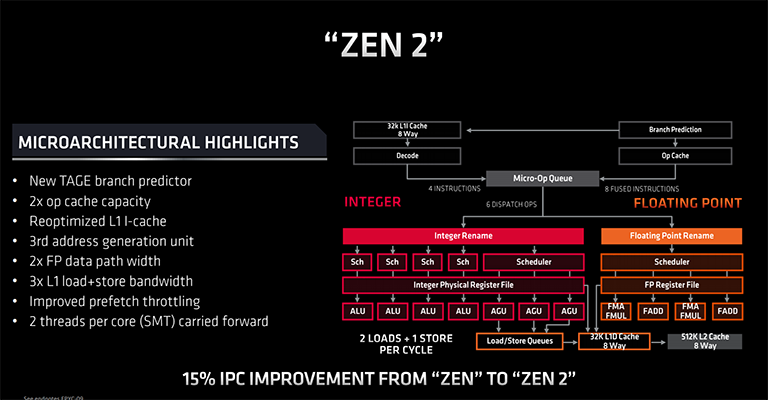

Built using the same 7nm production and Zen 2 architecture found on the desktop and server in various forms, it is worth spending a bit of time reading about just that in our prior analysis. Each CCD continues to hold two four-core CCXes, and the sum of the efforts is eight cores, 16 threads, enabling the company to double the core-and-thread count for both U- and H-series parts. That is a very significant statement with regards to multi-threaded performance. Think about that for a second; the CPU portion of a mobile APU able to harness 16 Zen 2-powered threads at no more than 15W!

There are differences between implementations, however, as you may recall that on a single Zen 2 CCX complex, desktop 3rd Gen Ryzen has 2MB of L2 and a whopping 16MB of L3 cache, and that is how the two-CCX Ryzen 9 3700X, for example, ships with a combined 36MB - 4MB L2 and 32MB L3. Mobile chips keep the same 512KB-per-core as desktop but reduce L3 from 16MB to 4MB, to effectively 1MB per core. The upshot is that the 8C16T mobile part has 24MB less cache than its desktop counterpart. Why, you may ask? The answer has to do with conserving die space for the GPU portion of the die.

On paper, then, compared to the previous mobile generation, Renoir doubles potential multithreaded performance from having twice the execution power, plus moves into an extra gear by way of an extra 15 percent dollop from the use of a better architecture. That's the same theoretical jump as from 2nd Gen and 3rd Gen Ryzen on the desktop. Impressive.

Renoir architecture - GPU

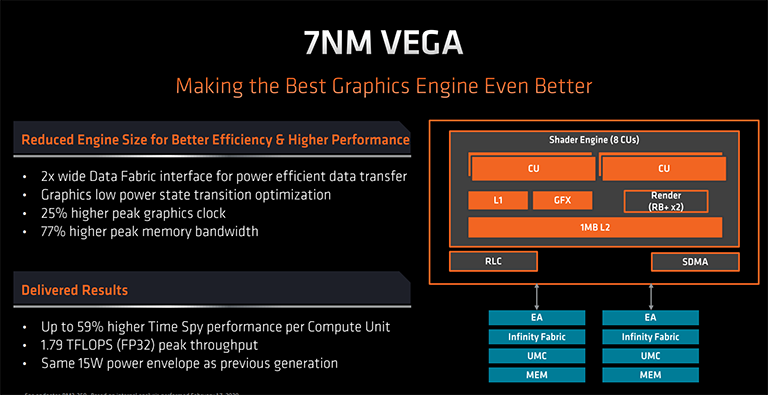

Last year's Zen+-based Ryzen 3000-series mobile APUs used the Radeon Vega architecture for the graphics component. Made sense as it was a proven design for desktop APUs. Given that a newer, better architecture is now present on the desktop in the form of Navi, you might assume Renoir chips would use it in some fashion. Wrong. In fact, Renoir reduces the number of Compute Units compared to the previous generation - from 11 to eight - so what gives?

AMD's use of Vega for Renoir is for time constraint reasons. Pulling a new CPU and GPU architecture into one mobile release, it said, offered too much risk. That's a shame, as Zen 2 and Navi make for ideal bedfellows.

Yet this iteration of Vega is not the same as its predecessor. AMD's engineers have rearchitected each graphics CU for more performance. First off, the move from 12nm to 7nm production offers higher peak clocks, up to 25 percent in certain cases, helping ameliorate the loss of CUs. Secondly, each CU has access to much faster memory - up to LPDDR4x running at 4,266MHz - faster internal data transfer, and myriad of other behind-the-scenes benefits that aid performance. The best 8-CU Renoir GPU is faster than an 11-CU Picasso.

AMD's made the graphics more efficient - doing more with less - but don't expect the same step-change in graphics performance as with CPU-bound tasks, where we're likely to see 2x the previous-gen numbers.

Renoir models

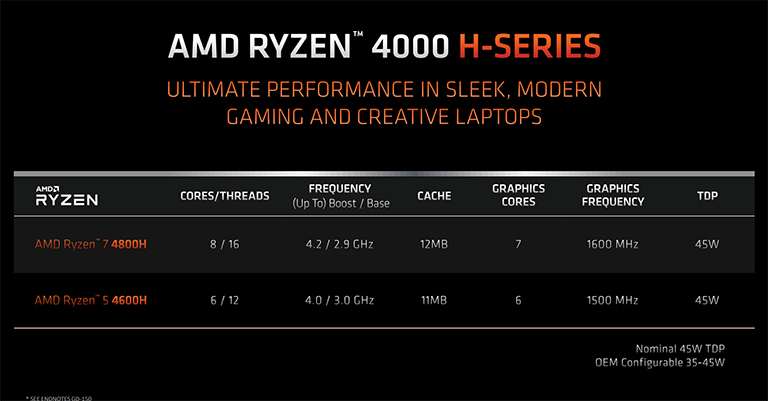

Looking at H-series APUs first, even though they feature the same integrated Vega graphics, they're primed for gaming laptops running with a discrete GPU in situ. The nominal power budget of 45W can be tuned in relation to the OEM's cooling capability. Turning it down naturally reduces frequency.

As standard, the two chips offer decent base-clock speeds. Comparing with last-gen Ryzen 7 3750H, which runs at 2.3GHz base and 4.0GHz boost on its four cores and eight threads, it is sensible to assume the Ryzen 7 4800H will be at least twice as fast, maybe 3x in certain applications that love Zen 2.

That isn't the fastest chip in the Renoir arsenal. AMD has since announced the Ryzen 9 4900H, plumbed with the same cores and threads but with higher speeds of 3.3GHz base and 4.3GHz boost. Its due to arrive in select laptops in spring 2020.

The U-series chips, meanwhile, also follow the same tact by increasing frequencies whilst remaining in a suitably frugal power state. Think about the Ryzen 7 4800U for a moment. Its baseline CPU performance ought to be similar to a desktop Ryzen 7 1800X from the original launch. Whichever way you cut it, that's impressive.

Keeping performance at maximum levels whenever needed, AMD is also introducing a technology called SmartShift, where, if laptop cooling is sufficient, extra power is allocated to the CPU or GPU in scenarios where it is warranted. Playing games or running CPU-intensive tests.

Renoir performance

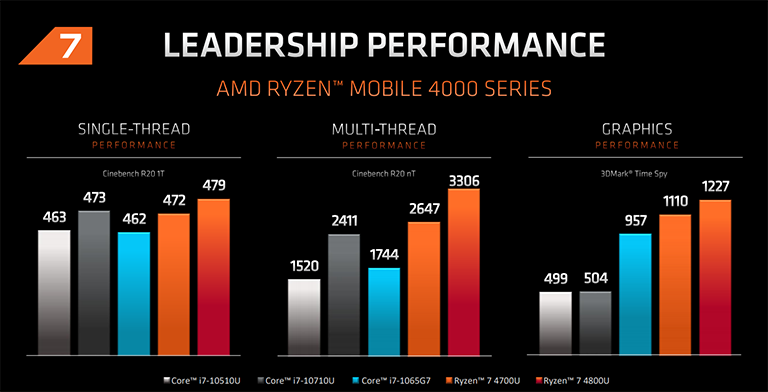

During a recent tech day, AMD offered a glimpse of Renoir performance by looking at the Ryzen 7 47/4800U's numbers against the latest chips from Intel. Take these numbers with a large pinch of salt, and we'll confirm exactly how fast the chips are when laptops arrive in the labs in the coming weeks and months.

That said, AMD reckons the headline 15W chip benchmarks at 3,306 in Cinebench R20 all-core test. That's pretty quick; our desktop 8C16T Ryzen 7 1800X only managed 3,598.

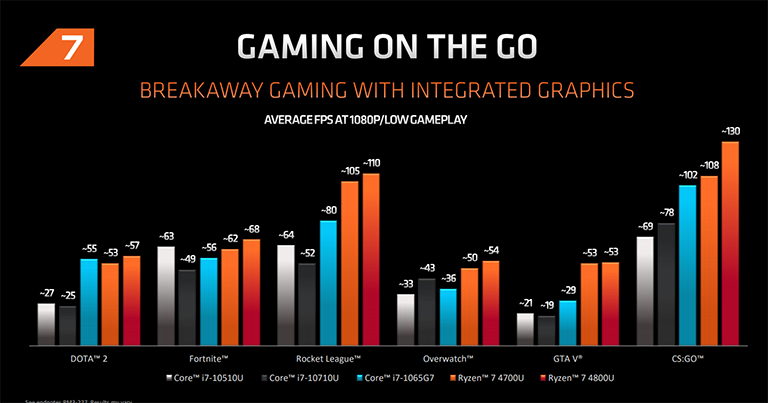

Intel has undoubtedly improved graphics capabilities with the Ice Lake generation of CPUs. AMD believes it is still some way quicker with its 8-CU Vega part in the Ryzen 7 4800U, offering on-the-go playability with some of today's most popular games.

It's all well and good when a company offers much better application performance from one generation to the next. AMD's Achilles heel in mobile hasn't been straight-line speed because the last-gen Ryzens were pretty good. Rather, it's with battery life, as we ably demonstrated in our Microsoft Surface Laptop comparisons.

Through faster clock control, better allocation of power budget to the workhorse cores, and quicker jumps in and out of low-power states, AMD reckons Renoir can spend longer periods in low-energy idle power states than ever before.

Using a combination of in-house benchmarks that detail day-to-day usage for a wide range of users, then normalising the results compared to a latest-generation Intel machine housing Ice Lake silicon, AMD further believes that it is a match for class-leader Intel in battery-longevity stakes.

There are more provisos to this kind of comparison than we care to shake a stick at. If we take it at face value, most AMD-powered ultrabooks of 2020 ought to achieve a real-world 10 hours-plus on a single charge, perhaps as much as 15 depending upon usage. We're super-eager to try the battery tests in the labs.

The Wrap

It's easy to see why AMD is so bullish for its mobile aspirations with the Renoir range of APUs. Offering over 2x the performance of the last generation through an 8C16T Zen 2-infused architecture, plus minor improvements in graphics, all wrapped up in the promise of significantly better battery life, it almost seems too good to be true.

We'll bear out AMD's claims as we test a Lenovo YogaSlim 7 equipped with a Ryzen 7 4800U APU in the coming weeks, but even if half of what's said turns out to be fact, the company's mobile aspirations are most definitely on the up.