Cuda to save the world

It's all about peace, love, understanding and parallel computing according to Nvidia CEO, Jen-Hsun Huang, speaking today at the GPU Technology Conference (GTC) in San Jose, CA.

Huang made sure to leave the audience in no doubt that parallel computing, for Nvidia anyway, was all about the Cuda architecture and the wider Cuda "ecosystem".

According to Jen-Hsun, over 90,000 developers are now using Cuda and 200 universities are teaching it as a subject in their computer science programs. Ever modest, Huang noted "This is the most pervasive parallel computing architecture known to man."

Industry on speed

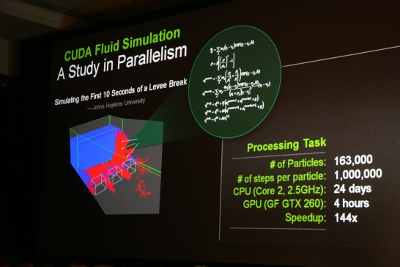

Discussing the impact of speed in changing industries, Jen-Hsun asked the audience to imagine what it would be like to be able to get from New York to San Francisco in just three minutes, or grow rice in just two days. "Being able to speed up your work 100 times, 200 times, changes industries," he said noting how transformative such changes would be.

Then, just as we were about to ask ourselves whether Nvidia was branching out into superspeed concords or rice paddies, Huang arrived at his point, declaring, "It's about heterogeneous computing, not homogeneous computing."

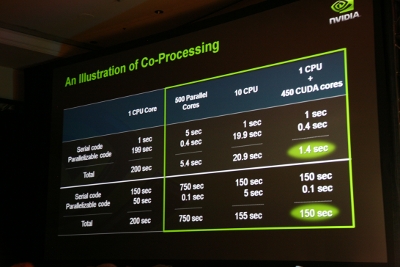

Huang posited that there was no reason why not to use the best CPUs and GPUs together to speed up computational tasks up to 200 times, showing a setup of one CPU combined with 450 Cuda cores. "It does no harm," he explained, adding that, in fact, in some cases, it could do rather a lot of good.

To prove his point, Huang invited David Robinson, CEO of Techniscan to the stage. Techniscan is a Utah-based company currently working to optimize ultrasound for early detection of tumours that could lead to breast cancer. Breast cancer, Huang reminded the audience, is completely curable if caught in time.

Robinson described how processing nine million Voxels and 120 million FFT calculations took four CPU clusters over an hour, but that just two Tesla C1060s took less than 30 minutes, equalling a GPU performance/price improvement of some eight times. "The idea that we can detect more cancers, smaller cancers, cancers in women that mammography doesn't serve well -- that's exactly our goal," said Robinson.