This is a guest blog by Ian Drew, Chief Marketing Officer and Executive Vice President Business Development for ARM. The views expressed in this blog are his and his alone. We invited Ian to share some of his thoughts on a hot topic of late: benchmarking for smartphones and tablets. Do let us know in the forums if you agree or disagree with his take on events.

Lies, Damn Lies and my Economics Lessons at School

When I was in my economics class at school, I remember my teacher telling me that there are "lies, damn lies and statistics". 30 years later, I started using that statement again regarding benchmarking. This blog is not about what makes a good or a bad benchmark, it is about how they are used and what they really mean. All benchmarks should be looked at in two ways:

1- If I was really going to use a device as a consumer, could I get the same sort of results as the benchmark?

2- Do I really care about some of the results? Are they measuring something that is important to me?

In the 25 years I have been driving, I've yet to match a 0-60 mph time or obtain an MPG figure that is quoted by the manufacturer. This doesn't stop me from driving or getting pleasure out of the experience. I just know that products in the real world don't perform as they do in artificial benchmarks.

Now all of that said, we do need metrics of how to measure one product against another or one solution against another. I've encouraged my teams over the past few years to try and make measurements real and repeatable, be conservative and make them relevant to an end-user, especially in relation to how they are using the product wherever possible.

Differentiation is key

I'd now like to talk about my passion in this industry: how to get economies of scale for low-power and high-efficiency consumer products such as smartphones and tablets. This is the basic premise of ARM and its business model. We are an IP company that enables the technology industry to differentiate on standard processor architecture and software. To do this, we continually strive to do better than both our competition and our previous products. As a Chief Marketing Officer, my favourite saying is: 'I want to make the news, not just report the news'. The past few months have shown how we can do this and here is where the benchmarks play out.

We tested the following consumer devices on a range of benchmarks, and we attached a power meter on the battery terminals to check the current and power usage. We used smartphones and tablets that consumers can buy today, not lab boards or test systems.

- Samsung Galaxy Note II (ARM-based quad-core Cortex-A9)

- TCL Y900 (ARM-based quad-core Cortex-A7)

- Samsung Galaxy S4 (ARM-based big.LITTLE)

- Lenovo K900 (Intel-based Clover Trail+)

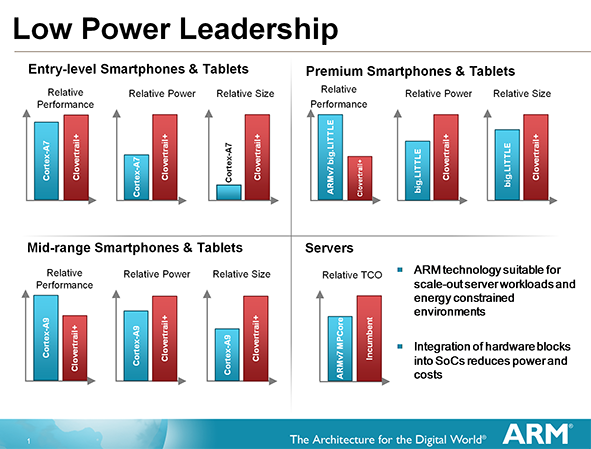

Better than the competition in the low-power space

We start at the low-end of the smartphone range, something you expect to pay about $100-$150 for. To achieve this price, you need to minimise the cost of all the components, including the SOC, screen, memory, plastics and battery, and still leave a profit for the OEM. To develop a low-cost SOC with the right performance and profitability requires a lot of companies to work together. You need a high-throughput fab, at 28nm, you need an OS ready to make best use of the SOC, and you need a supply chain that is efficient and effective.

The Cortex-A7 processor is ARM’s most energy-efficient core, but when we looked at the benchmarks we had to double- and triple-check them because they were so good. Here, in a nutshell, is what we found:

- It's about 95 per cent the performance of an Intel Clover Trail+

- Consumes less than half the power of a Clover Trail+ when screen power is subtracted

- The CPU area is about 20 per cent the size of the CPUs in a Clover Trail+

This, to me, also shows that the economics of a disaggregated industry (ARM) cannot only compete, but outperform, a vertical industry (Intel).

Cortex strong in the mid-range, too

We measured again, but changed the comparison to a mid-range platform solution from another ARM-based silicon vendor. This time we measured a Cortex-A9 quad-core in 32nm versus the Clover Trail+, to see the power/performance difference. We saw the following:

- 20 per cent-plus improvement in benchmark performance

- 40 per cent saving in measured power

- 50 per cent saving in area

Again, very good performance from one of our most mature but biggest-volume products. Still, years after launch, the ARM Cortex-A9 is a market leader.

When you then start to look at some of the new SOCs and the way they have implemented our new big.LITTLE technology, the comparisons should really be with the Intel Core family of products. With the Samsung Galaxy S4 beating the Clover Trail+ by, on average, 200 per cent* and yet using only 70 per cent of the power, it was, frankly, no contest. I fully expect to see a slew of big.LITTLE-based SOCs in the market this year. It's clearly the best way to save power, by having the right-size core for the right workload.

My takeaway from this these past few months of work is:

- Don't trust individual benchmarks, because you need to use a broad range to get a good feel for how a phone or tablet will work in the real world

- Consumers want higher performance but at lower power and will continue to demand this for the next few years

- The ARM business model allows the best and brightest companies to thrive in a horizontal market. This is still the best way to drive innovation in the industry

* Benchmarks used were: BrowserMark, Geekbench, Kraken, LinpackST, Octane, PeaceKeeper, Quadrant Advanced CPU, SunSpider, V8, Vellamo-html5, Vellamo-Metal.