A new keyboard called the IKB, or the 'intelligent keyboard' is touted as the latest method to provide better cyber security against people gaining unauthorised access to computers. The device filters out strangers, only responding to the genuine users' biometric password as it analyses the unique patterns in their keystrokes. It also generates electricity with every key press which is then used to power the keyboard and optionally provide power to other attached peripherals.

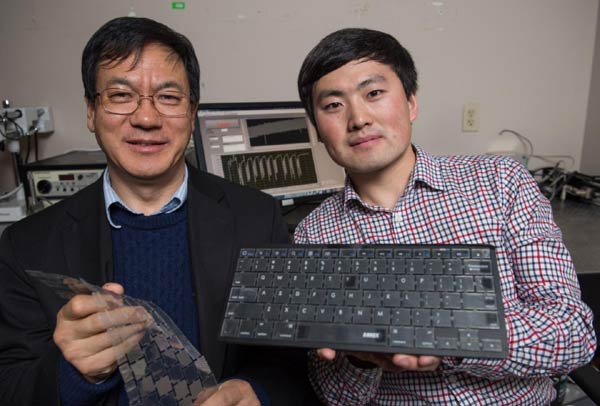

Developed by researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology, University of California Riverside, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the self-powered keyboard harnesses the electricity created by the touching of its multi-layer plastic keys to power itself and attached peripherals. The researchers say that by touching the key, the user creates a current that is sent through the layers to create an electric charge, an effect known as contact electrification. The layered material can be easily attached to a regular keyboard so in the future your current favourite keyboard could be IKB-ified.

"This intelligent keyboard changes the traditional way in which a keyboard is used for information input," says Zhong Lin Wang, a professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. "Every punch of the keys produces a complex electrical signal that can be recorded and analyzed."

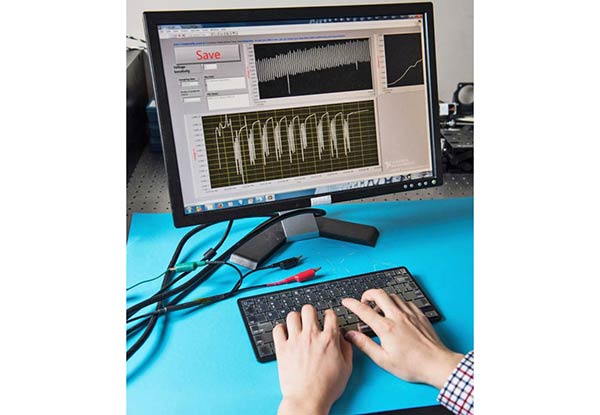

The IKB senses typing patterns, the level of pressure applied to keys and user typing speed, accumulating data that is enough to distinguish one individual from another. These unique typing styles could be used to provide a new kind of biometric authentication.

"This has the potential to be a new means for identifying users," says Wang. "With this system, a compromised password would not allow a cyber-criminal onto the computer. The way each person types even a few words is individual and unique."

The team tested the device on 104 people, where they were split into two groups. The 'clients' group were asked to provide their biometric password by typing the word 'touch' four times on the IKB whilst the 'imposters' would attempt to gain access by imitating a similar pattern. Results of the test show that the IKB had a very low error rate of 1.34 per cent in identifying the real user against potential thieves. That's not bad for a 'frictionless' extra level of security.

The IKB is still in the early stages of development, and the team believes that with the help of investors, the keyboard can be bought to the market in two years. The durable keyboard is dirt, oil and water-proof and could have a wide variety of potential applications including for cash registers, ATMs and network security systems.