What's new, pussycat ?

A visual inspection is usually a decent method in differentiating CPUs. Let's take a look at what Intel dubs the 'Extreme Edition'.

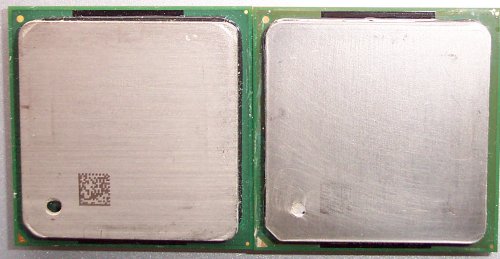

There's not too much information contained on the heatspreaders, unfortunately. The CPU on the left is a bona fide Intel Pentium 4 3.2GHz Engineering Sample. It communicates with a compliant North Bridge at the usual 800MHz and features the lush Hyper-Threading technology inherent in most new P4s. The CPU on the right, however, is the Extreme Edition. The heatspreader was largely unmarked, save for a batch number (0121, incidentally) near the Intel mark.

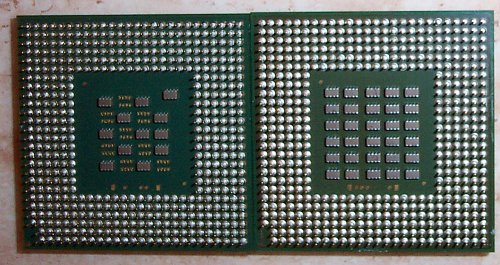

A few differences emerge on the rear. The Extreme Edition, on the right, features a greater number of capacitors than a regular Northwood. The pin count, obviously, has been kept intact, so it just slips right into a Socket-478 form-factor. This, then, begs the question of exactly what's different, and what's Intel up to ?. Let's play spot the differences.

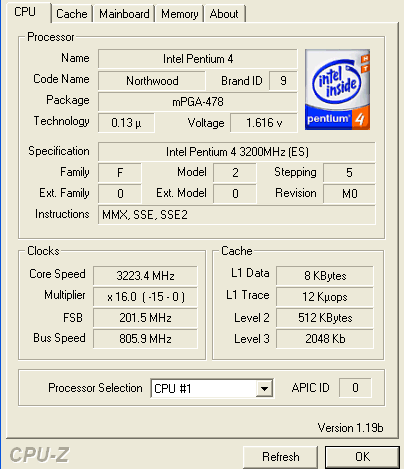

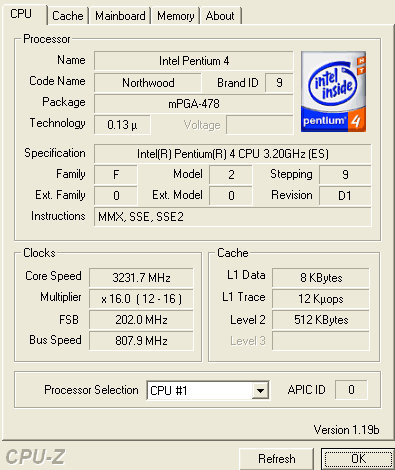

Both are Engineering Samples but the Extreme Edition, on the left and in addition to the regular Northwood, features 2MB of Level 3 cache and, unsurprisingly, is identified as a M0 stepping. One would be correct in thinking that this stepping is in current use now. The 'Gallatin' workstation-class Xeon uses exactly the same cache configuration, and it appears as if it has been morphed into a Socket-478 form factor and been made to run at 3.2GHz with a 800MHz FSB. Further investigation shows no architectural differences between the two Intel CPUs pictured above.

Loads of cache

The primary reasons for increasing the amount of on-chip cache can be summarised as follows. On-chip cache in modern CPUs runs at the same speed as the core frequency. In this case, that's no less than 3200MHz. Larger levels of cache allow the CPU to hold bigger portions of code nearer the execution units. CPU architecture is primarily focused on reducing delays associated with keeping the CPU waiting for data. Having it ready on-chip, via intelligent prefetching algorithms, therefore, reduces the need to keep trawling back to system memory, which, frankly, is an order of magnitude slower than the CPU's cache speed. Games use large chunks of code that have to be hauled from system memory once the CPU demands it. Reducing the instances that data has to be pulled from system RAM, through the MCH and to the CPU is a sure-fire method of increasing performance in memory-intensive applications. Level 3 cache has a slightly higher latency than Levels 1 and 2; that's to be expected, but it's still considerably faster than conventional memory latency. One interesting test will be to see just what kind of latency is present in the 512kb - 2.5MB areas, as that's where the Extreme Edition should eke out an advantage over the regular CPU.

That's the key. Not all applications will benefit from increases in cache size or speed. It depends on the particular nature of the application, but as Intel is targetting this CPU at enthusiasts and gamers, we fully expect it to realise a significant performance advantage over Mr. Ordinary 3.2GHz.

If having a copious amount of on-chip cache is a good thing, which it is, what's stopped Intel from applying this strategy before ?. The simple and unavoidable answer is sheer cost. Reserving die space for cache is an expensive, expensive business. The regular 3.2GHz Northwood packs in an impressive 55 million transistors, many of which go to feeding the 512kb of Level 2 cache. Its die size is reckoned to be 131mm², based on a 0.13-micron manufacturing process, and manufactured using 300mm wafers. Adding 2048kb of Level 3 cache has, Intel proclaims, boosted the total transistor count to around 167 million and, in turn, the die size to 213mm². Basic maths informs us that the Extreme Edition is going to be one expensive CPU. You just don't make that many on 300mm wafers, and someone has to foot the bill. The consumer, most likely. The theoretical advantages to masses of on-chip cache are painfully obvious, but so is the cost. Cynical observers may smirk at Intel's attempts to gatecrash AMD's party with this new hither-to unseen CPU. Intel is adamant that this is the first in a long line of Extreme Edition CPUs that will be available in limited quantity. The 3.2GHz Extreme Edition, of course, supports Hyper-Threading.

Time to test, folks.