Scientists based in the United States and South Korea have designed a new cooling methodology which adopts a 'porous membrane' design and is expected to be of benefit in applications such as PC laptops, IoT devices and data centres. The surprising thing about this advance is that it was inspired by what might be described as a 'living fossil' insect - the springtail - which has been around for approx 400 million years.

In an article published by IEEE Spectrum, it is explained that over millions of years springtails evolved a water-repellent skin through which they can breathe, even when their environment is saturated with rainwater. Scientists concluded that a similar porous membrane design could be used to stop electronic systems from overheating through evaporative cooling.

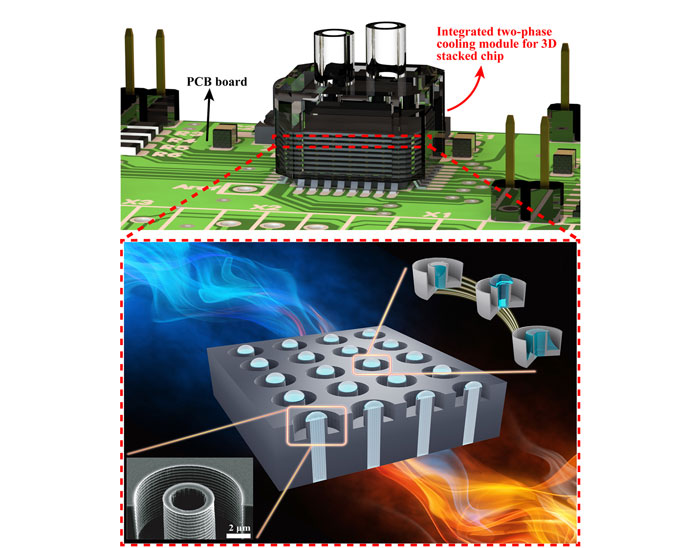

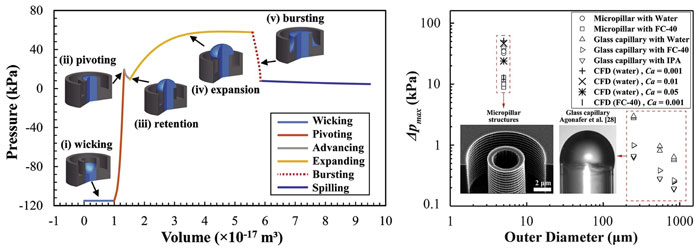

The springtail's sharp-edged skin surface compartments resist the advance of liquids and can help contain the flow of liquids. Inspired by this property in cooling surface design, dielectric liquids, which tend to easily wet any solid surface, can successfully be contained, can be used under certain test conditions. "Such a method is particularly promising in interlayer two-phase cooling for heat removal in 3D stacked chips, where dielectric liquid is required to avoid risks associated with water in electronic components," Damena Agonafer, an assistant professor in mechanical engineering and materials science at Washington University in St. Louis, said.

Agonafer thinks the tech will go on to significantly improve the cooling efficiency in a wide variety of applications such as data centres, and decrease the electronic footprint compared to traditional cooling technology. These are both highly attractive benefits. However, we are still at an early stage with the man made sharp edged porous membrane only able to handle fairly tame liquid behaviour involving a "very slow flow rate". For a truly practical cooling solution for 'hot' electronics it needs to be tuned for a "high mass flow rate."

With various tech challenges ahead the research team remains optimistic. The scientists have received backing from the likes of DARPA and Cisco to continue their work. It is estimated that another 3 or 4 years of research and development are needed before commercial application. Importantly, the scientists assert that the required layers of liquid-filled micro-pillars in silicon would not be expensive to create in a modern fab.

Further information on this project is available via the 15 March 2018 online issue of the Journal of Colloid and Interface Science.