The how

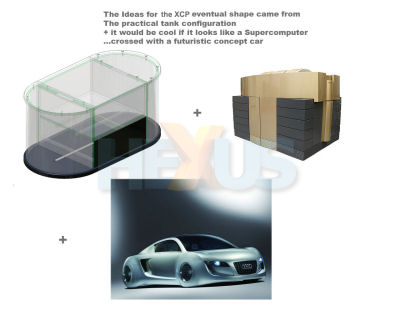

First mooted as a concept PC around two years ago, Armari wanted the super-PC to be a fully-functioning model that would make it, ideally, into a low-volume production run.Effective and efficient cooling of the components was key, clearly, and the design concept, shown below, was how the company envisaged the system to look. A fusion of two styles, evidently.

Supercomputer-cum-concept car, huh? The idea was to shoehorn a high-end system into the wholly custom chassis - where over 100 parts have been in-house-designed - and cool it via a variety of means, including LN2, liquid fluorocarbon immersion, TEC, and phase-change, depending upon model.

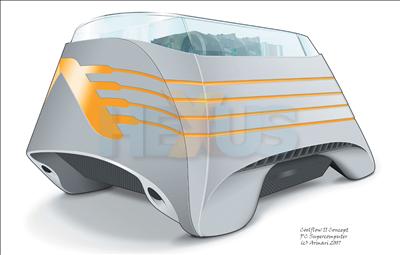

The picture, below, shows the concept mock-up of the system - different to pretty much any other high-end system out there.

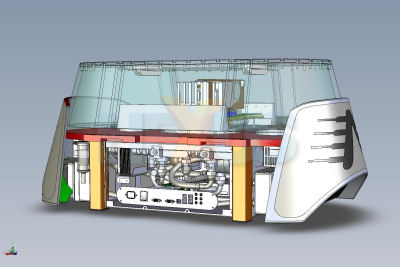

Armari then spent six months working with The Product Works - a professional product-design consultancy - to get a complete SolidWorks CAD model, ensuring that the grounds-up cooling and component logisitics would work correctly.

Want to see just how complex top-of-the-line, custom cooling can be, and just why responsible firms spend mucho dinero on computer-based modelling before wielding the hacksaw and torch?

Above is a picture of the computer-aided design - one that 's closer to the final-specification model.

Note the busy, industrial-looking nature of the cooling apparatus at the bottom? It's all there for a purpose, naturally.

A further six months were spent on manufacturing a working prototype. The system was initially slated to use Intel's maligned V8 platform, but was later changed to the current Skulltrail - incorporating two quad-core CPUs natively running at 3.2GHz on a motherboard that supported four graphics cards - when the design became available.

A little-known fact is that Armari's technical director, Dan Goldsmith, being the eccentric chap he is, bought a decommissioned Cray supercomputer - used in the Cold War - a while back. Cray's extra-large computers (by today's standards) required some serious cooling, as you would expect, and Cray engineered some class-leading liquid cooling to keep the voluminous beast operating within tolerances.

Dan has used the inspiration from Cray's research, and indeed the coolant itself, which works in a temperature-range of -110C through to 90C, as a base for the XCP (eXtreme Concept Prototype) - the total immersion model.

Armari's project means that almost everything is custom-designed for the purpose, including blocks, monitoring PCBs, piping, wiring and, of course, chassis. In fact, there's nothing much which isn't grounds-up, which is cool, if you'll excuse the pun.

The LN2-equipped model will feature greater internal complexity as Armari seeks granular control over the exact temperatures of the CPUs.

Here's the physical manifestation of almost two years of work. The XCP has been architected as a no-holds-barred performance PC that's also suitable for running on a 24/7 basis. Internal layout is such that performance is the most important criterion, with, currently, servicing and layout playing subservient roles.

Strictly an engineering-sample machine at the moment, Armari reckons that there's a market for a limited number of systems to be sold in retail form, once qualification is complete. A liquid-cooled model, with appropriately extravagant hardware, will cost in the region of £10,000, we're told.

We've given you a sneak peek in to an ongoing project that aims to revolutionise bespoke, high-end PCs.

We will next look at exactly how the cooling works and when we'll see the finished model.

Right now, it's almost impossible to say whether this is one man's failed foible or if there's significant merit in the design.

If that's whetted your appetite for some high-end fun, head on over to HEXUS.tv for some visual treats.