Fighting New Foes

Is it too early to call Intel a semiconductor manufacturer in decline? Perhaps, yet in the consumer space there's no ignoring the recurring signs. UMPCs barely got going, netbooks have been forgotten, and Ultrabooks aren't doing enough to stall the steady decline in PC sales.

For the likes of Intel and Microsoft, who have long enjoyed the benefits of a symbiotic relationship, these are worrying times. Today, designing the highest-performance chips doesn't guarantee success, and while Intel remains king of the desktop performance crown, there's little competition and seemingly even less desire to raise the bar. Had AMD found a way to Bulldoze Intel's Ivy Bridge, we most probably would have seen the arrival of an enthusiast-orientated Ivy Bridge-E, but such premium solutions are being neglected as a new battle takes place elsewhere.

Forget Moore's law, it's sod's law that another three-letter foe beginning with the letter A is proving to be a thorn in Intel's side. The decline in PC sales can be directly attributed to the rapid increase in sales of devices powered by cost-effective, low-power ARM microprocessors. Smartphone and tablet sales continue to soar and here's the real kicker: consumers don't care what powers these devices, what matters is that they're typically cheaper than laptops, ultra-portable, and able to offer genuine all-day battery life.

With PC and mobile converging quicker than ever before, Intel needs to reassert its presence in portable devices with an architecture that can scale across multiple platforms. That quest begins today with the introduction of the fourth-generation Core processor family, codenamed Haswell.

4th Generation Intel Core Processor Family

Launched as a successor to last year's Ivy Bridge, Haswell follows Intel's tick-tock release schedule, where a tick (Penryn 2008, Westmere 2010, Ivy Bridge 2012) primarily insinuates a shrink in manufacturing process, and a tock (Nehalem 2009, Sandy Bridge 2011, Haswell 2013) implies a major architectural refresh.

The annual upgrade cycle remains as relentless as ever, however Haswell arrives with a distinct overture. Instead of promoting core counts or frequencies - once the crucial elements of a new Intel processor generation - the fourth-generation family is being delivered with the promise of a better experience.

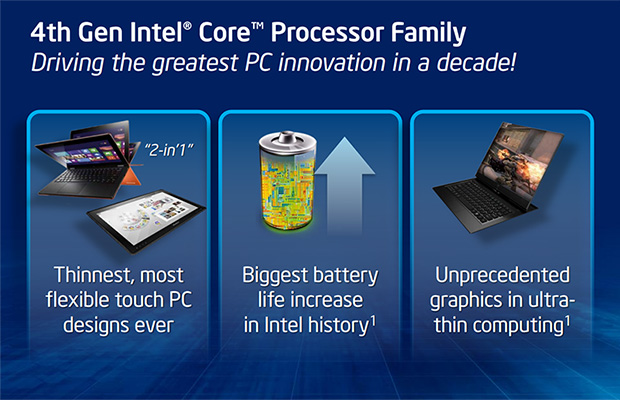

Intel clearly isn't shy in marketing Haswell's potential. We can look forward to a new class of thin, two-in-one touch PCs that offer the "biggest battery life increase in Intel history" and "unprecedented graphics in ultra-thin computing," says the chip giant.

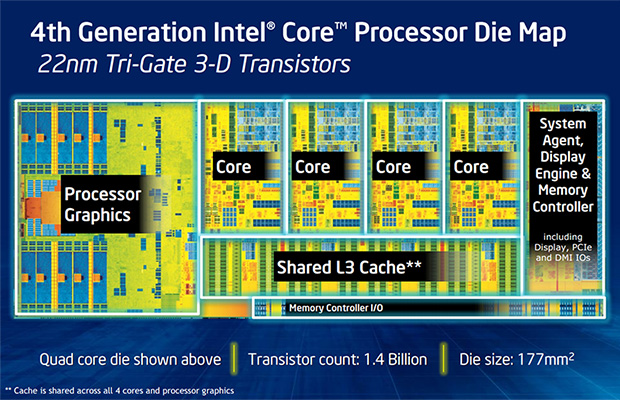

Lofty claims indeed, so how will Intel effectively reinvent the PC? From a manufacturing point of view, not a whole lot appears to have changed. Looking at an overview of a quad-core desktop Haswell die, the chip is very similar to incumbent Ivy Bridge; it's built using the same 22nm Tri-Gate process and continues to carry 1.4-billion transistors, albeit in a slightly larger 177mm² die (up from 160mm²). Details on dual-core chips are due to be released in the very near future, though don't expect any surprises there.

The increase in die size will result in a higher per-CPU cost for Intel - it simply can't create as many chips from a single wafer based on the same process geometry - but while the chip configuration looks familiar, Haswell marks a shift in the way Intel designs for various platforms. The company's fourth-generation architecture is more modular in nature, allowing it to meet a wider range of thermal design points and arrive in the market in various shapes and sizes.

In 2013, we will see Haswell appear in four unique categories; for desktops, for laptops, for Ultrabooks and for tablets/detachables. Complicating matters, Intel now has three important factors that need to be identified in branding - power consumption, graphics performance and compute performance - and the existing Core i3, Core i5 and Core i7 product lines will consequently be expanded through at least a dozen unique suffixes spread across the entire range.

What's clear is that Intel is focussed on efficiency. Had Nvidia been at the Haswell helm, we may have seen a doubling in die size in an effort to increase transistor count and deliver the maximum amount of performance, no matter what the cost in terms of power. What we're seeing today is Intel moving in the opposite direction: the company is taking its latest and best-performing architecture and attempting to refine it to such an extent that it seamlessly fits in everything from tablet to server.