Published in a recent edition of the Advanced Energy Materials journal, research from US Northwestern University displays findings on a new approach to Lithium-Ion battery technology that can offer 10x the capacity and 10x the charging speed over currently available batteries.

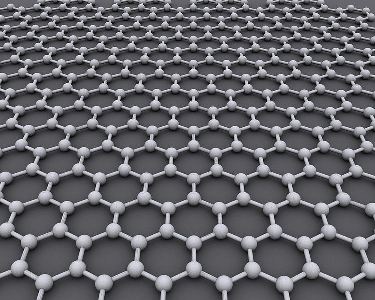

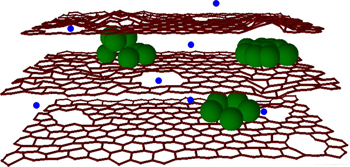

In existing Li-ion batteries, charge is stored at one end of the device, the anode, by packing lithium ions between sheets of graphene, a single-atom-thick sheet of carbon. This approach is not unlike storing water in a dam, with the lithium ions taking on the roll of the water. These sheets are able to accommodate a single lithium ion for every six carbon atoms; Northwestern proposes the use of silicon clusters in-between these graphene sheets, as silicon is capable of storing four lithium ions to each silicon atom, a greater density of energy, or more water in the dam.

Silicon had been considered for a long time for its uses in batteries; however previous attempts sought to replace graphene layers with layers of silicon; the issue here is that silicon expands and contracts excessively during the charging process and fragments/cracks, rapidly reducing charge capacity. Northwestern's approach of using small clusters of silicon between the graphene layers as opposed to replacing them was, therefore, a very smart move.

Another limitation of current batteries is the charging rate. Currently, the lithium ions must travel around each sheet of graphene to reach the next one, taking time and causing bottlenecks as ions clash in close quarters. Northwestern's approach has been to create small, 10 to 20 nanometre holes in the graphene sheets, to allow for more direct travel routes without sacrificing the overall functionality of the sheet, which is to attach to the ions and prevent the newly included silicon atoms from escaping.

Overall, some very promising steps forwards, though currently, this new technology does still lose charge over time, with the improved 10x capacity dropping to 5x after 150 charges. Mind you, if you find yourself charging your phone once per day, this new technology should enable charging of once per ten days initially, dropping to once per five days after 150 charges; given how infrequently a device would need charging, it would take around three years to reach 150 charges under these circumstances, at which point you still have five fold capacity over a current battery.

Researchers suggest that this technology could be seen in the market place in the next three to five years. A promising future for portable devices indeed.