Armari's T90

The T90 is maybe the most outrageous supercomputer, in terms of appearance at least, that Cray ever created. The T90 is another MPP supercomputer with custom vector processing units on the CPUs. While the T3D uses standard DEC Alpha processors, the CPUs in the T90 are Cray's own design, implemented in ECL. The CPUs themselves come clocked at 450MHz and have two vector add pipelines and two vector multiply pipes. Each can output a result to the data bus per clock cycle, so the CPUs in a T90 are capable of 4 floating point operations per clock. The famous per-CPU flops (floating point operations) rating for the T90 is therefore 1.8Gflops/sec.Memory bandwidth per CPU is 24GB/sec and again, due to the topology of the CPU interconnect and the way memory accesses can work in a T90 mean that scales per CPU. In a full T932 implementation of the T90, containing 32 processors, that's nearly 800GB/sec of CPU-to-memory bandwidth and a peak floating point performance of nearly 58Gflops/sec. The T90's per-CPU memory bandwidth is down to the fact that the CPU's vector units work optimally if allowed to read two operands from memory and write one result back to memory, per cycle. Using 128-bit vector data, that's a 384-bit/48-byte per second bandwidth requirement. The T90's memory controllers were therefore designed to fulfil that requirement, tripling the memory performance of the C90 vector MPP supercomputer systems that the T90 was designed to replace.

Cray's earlier reluctance to support the IEEE 754 floating point data standard was dropped on the T90's CPU, with it fully supported for the first time. While Cray's J90 architecture had a separate scalar unit on the CPUs, the T90 dropped that and replaced it with a small scalar cache, with the actual scalar calculations performed by the vector logic. The dropping of the unit allowed them to dedicate die space to other performance enhancing features, with the scalar performance of the T90 not affected too much due to the addition of the cache.

The T90's physical presence matches its fearsome computing power. If you've never seen a T90 before in person, even if you've seen one in pictures, it's something of a shock.

The cooling system designed for the T90 is the main reason for its appearance. All the system, I/O and memory processor boards in the T90 are fully submerged inside an internal cooling tank. The coolant is 3M's Fluorinert PFC and fully laden with the liquid, the T90 is some 10 metric tonnes in weight. Slightly more than your average ATX computer these days.

There was no air-cooled option for the T90, it was liquid-cooled or nothing. The T90 is what inspired Armari to persue liquid PFC (perfluorocarbon) cooling for the modern PC. Their InertX coolant range is a PFC similar to Fluorinert, but not manufacturered or licensed from 3M. So the cooling ideas in Cray's supercomputers live on today via companies like Armari. While you won't see submerged cooling using InertX or Fluorinert these days (outside of overclocking endeavours like Armari's PCMark04 record breaking machine), it's usable in regular liquid cooling systems and offers the unique chemical properties of the liquid as an advantage over water as the coolant.

You access the cooling area in the T90 by lifting up the top panels, which are on fully hydraulic lifters, opening the side panels like two giant swing doors, and unscrewing retaining bolts that hold the panel to the side of the cooling tank in a pressurised, air and liquid-tight seal. Dan told me a story about an intern at Cray once undoing the access panel as the system was full of Fluorinert and pressurised. The pressure release was enough to shoot the access panel, with intern attached, across the room, the Fluorinert (some four tonnes in weight!) pouring out onto the floor. Ouch.

With a system so massive, the T90 needs to be lifted by heavy lifting gear each time Dan needs to move it somewhere else in the building, even if that's 6 inches from where it currently sits to get a new rack cabinet in the testing area. Those six inches of movement used to cost him multiple thousands of pounds at a time, so he wisely invested in the lifting equipment needed so that he can somewhat arrange to have the T90 moved himself without the high cost.

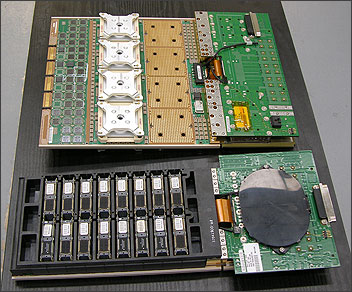

If I were so inclined, and I'm not a small guy, I could quite easily climb inside an empty T90 chassis, into the cooling chamber. And partially empty was what Armari's T90 was until recently. Collecting the chassis is all well and good - they are spectacles of computing history in their own right - but Dan likes to have them functionally complete, even if they'll never crunch another vector calculation again. So having secured the T90 chassis from a UK institution, as it and its sister T90 were being decommissioned, he set about laying the groundwork for obtaining the CPU, I/O and memory boards needed to build the T90 into a full 32 CPU T932.

A full T932 on launch would cost customers of Cray a cool $39,000,000 US.

Jesus. Christ.

So Dan spent another sum of money (and lots of begging to Cray apparently!) securing the missing boards needed to complete the T90 and he'll soon have it reassembled.

I've not completely conveyed the spectacle that is a T90 chassis. Armari's is finished in a bling-bling gold colour and it truly does look like an Egyptian sarcophagus. It's massive, disgustingly heavy and the way the top panels open on their lifters, somewhat like the gullwing doors on a McLaren SLR supercar, makes you giggle like a schoolboy that's just seen his first pair of bare boobies.